On May 28, 1830, Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law. The passage of this Act created a new era in US-Indian relations. For centuries, colonialist powers had undermined the national identity of Indigenous people and sought to replace it with a racial identity in line with a European worldview. With the Indian Removal Act, race moved to the forefront of US-Indian relations.

Land cession treaties - the essential condition for US expansion - were nation-to-nation agreements. Over time, however, the narrative of these territorial transfers became racialized. A delusional but popular racial definition of Indians came to full fruition in the Indian Removal Act in which the elimination of a race from US territory became official US policy. Land cession treaties - the essential condition for US expansion - were nation-to-nation agreements. Over time, however, the narrative of these territorial transfers became racialized. A delusional but popular racial definition of Indians came to full fruition in the Indian Removal Act in which the elimination of a race from US territory became official US policy.

Shortly after the Louisiana Purchase (1803), the US had begun pressuring tribes to “relocate” to western territory where the US claimed dominion but had not yet moved its own citizens. The Removal Act authorized the President to negotiate Indigenous cessions of eastern land in exchange for new western homes. During the next ten years, 86 treaties were negotiated (a quarter of all treaties in history), and all of them were related to Indian removal. No trade agreements, no military alliances, no peace treaties: the focus of US policy came to focus exclusively on ethnic cleansing.

Prairie Du Chien, 1830

The first treaty after the passage of the Indian Removal Act was another multinational conference at Prairie du Chien. Under the guise of brokering peace among many nations, William Clark engineered a cession of the western third of present-day Iowa. He promised at the treaty that all of the nations could use it as a common hunting ground; his report to Washington promised that hunting there would fail within three years, and the land could be used to relocate eastern tribes. US signers of the treaty included founders of Davenport, Iowa (George Davenport, Antoine Leclaire, Captain William Gordon); members of the Clark/Chouteau extended family; holders of several enslaved people who would rise to fame (John Sanford: Dred Scott; David D. Mitchell: Lucy Delaney); and Jacob Halsey, a clerk who would later start a small pox epidemic that killed nearly 40% of the population of the Upper Missouri region.

Chickasaw and Choctaw, 1830-1837

In 1830, the Chickasaw met Andrew Jackson in Franklin, Tennessee to negotiate the cession of their homelands. Jackson told them that their best hope for surviving the onslaught of white settlement would be to move away and “be forgotten.” US treaty commissioners John Eaton (Jackson’s Secretary of War) and John Coffee (a business partner with Jackson and the husband of Jackson’s niece) negotiated a treaty in which the Chickasaw could remain in their homeland, primarily in Alabama, until “suitable land” could be found for their removal in the west. The commissioners then traveled to Dancing Rabbit Creek in Mississippi, where they negotiated a 15-million-acre land cession from the Choctaw. The treaty split the nation into those who would undertake the arduous, deadly walk to Oklahoma, and those that would remain in Mississippi as citizens of the US. In 1832, Coffee re-negotiated the treaty with the Chickasaw. Their homeland would be allotted to individual members pending removal to a still-undetermined location; all of their homeland would be sold to raise money for them to buy land and relocate. In 1834, Eaton again negotiated Chickasaw removal, refining the stipulations for the sale of their land. This treaty also allocated extra parcels of land to be sold for the benefit of Chickasaw leaders. R. P. Currin, who signed the 1830 Choctaw and Chickasaw treaties, was part of a cabal that located these extra parcels near town sites and salt springs, and then bought them from the Chickasaw individuals; Currin, for instance, paid $500 for a salt spring and sold it for $10,000. In 1837 the Chickasaw purchased land from the Choctaw in the west and paid for their own relocation. In 1830, the Chickasaw met Andrew Jackson in Franklin, Tennessee to negotiate the cession of their homelands. Jackson told them that their best hope for surviving the onslaught of white settlement would be to move away and “be forgotten.” US treaty commissioners John Eaton (Jackson’s Secretary of War) and John Coffee (a business partner with Jackson and the husband of Jackson’s niece) negotiated a treaty in which the Chickasaw could remain in their homeland, primarily in Alabama, until “suitable land” could be found for their removal in the west. The commissioners then traveled to Dancing Rabbit Creek in Mississippi, where they negotiated a 15-million-acre land cession from the Choctaw. The treaty split the nation into those who would undertake the arduous, deadly walk to Oklahoma, and those that would remain in Mississippi as citizens of the US. In 1832, Coffee re-negotiated the treaty with the Chickasaw. Their homeland would be allotted to individual members pending removal to a still-undetermined location; all of their homeland would be sold to raise money for them to buy land and relocate. In 1834, Eaton again negotiated Chickasaw removal, refining the stipulations for the sale of their land. This treaty also allocated extra parcels of land to be sold for the benefit of Chickasaw leaders. R. P. Currin, who signed the 1830 Choctaw and Chickasaw treaties, was part of a cabal that located these extra parcels near town sites and salt springs, and then bought them from the Chickasaw individuals; Currin, for instance, paid $500 for a salt spring and sold it for $10,000. In 1837 the Chickasaw purchased land from the Choctaw in the west and paid for their own relocation.

Menominee and “New York Indians,” 1831-1839

The Menominee of Wisconsin signed a treaty in Washington in 1831 with Secretary of War John Eaton. His co-commissioner was Samuel Stambaugh, an Indian agent from Green Bay at that time, who made a career out of kick-backs from the American Fur Company. In this treaty (considered fraudulent by the Menominee leader Oshkosh, who was absent) the Menominee ceded 2.5 million acres in Wisconsin. Congress unilaterally added that tribes from New York, starting with the Christianized Stockbridge-Munsee bands, would be relocated to Menominee territory, over the objections of the Menominee. Two subsequent Eaton-Stambaugh treaties (in 1831 and 1832) addressed the dissatisfaction of all of the tribes involved. The Stockbridge-Munsee bands ceded part of their Wisconsin lands in 1839, and part of the population moved west. Meanwhile, other “New York Indians” (or Six Nations) agreed to move to Wisconsin in 1838. A special provision for the Seneca in this 1838 treaty, in which a land speculation company directly acquired their reservations, complicated the arrangement, and led to subsequent treaties in 1842 and 1857 by which Seneca bands remained in New York.

Gardiner and Ohio, 1831-1836

Reservations in Ohio were ceded by the Seneca, Shawnee, Ottawa and Wyandot in five treaties negotiated by James Gardiner in 1831 and 1832. A newspaper owner, Gardiner was nominated by Jackson to be a land agent in Ohio, but when his appointment was denied due to his “frequent intoxication” he became an Indian agent. In treaty negotiations Gardiner so overstated the danger of retaining tribal reservations in Ohio that the Senate investigated these treaties as outright frauds. He was then placed in charge of conducting Ottawa and Seneca removal, but was soon fired for incompetence. A subsequent cession of a reservation by the Wyandot in 1836 was negotiated by another former newspaper owner, land speculator John Bryan.

Castor Hill Treaties, 1832

At William Clark’s summer home in Castor Hill, Missouri in 1832, the Kaskaskia, Kickapoo, Shawnee and Piankeshaw ceded all of their lands in Missouri and Illinois. Although some of them had already been relocated to west of the Mississippi, they were to move further west beyond the lines of white settlement, into present-day Kansas and Oklahoma. Clark’s son, step-son and brother-in-law were among the signers; Clark’s treaty-signing and business partner, Auguste Chouteau, had died in 1829, but his son was at Castor Hill. These treaties established the borders of Missouri as the limit of white settlement, beyond which all nations in the east would be relocated.

Muscogee and Florida Tribes, 1832-1833

In 1832, the new Secretary of War,

Lewis Cass, negotiated a removal treaty with the Muscogee. Three million acres would be ceded in exchange for money to relocate. Another two million acres would eventually be allotted individually to Muscogee people who intended to stay as citizens in the hostile environment of Alabama. In his new cabinet position, Cass filled the treaty signing room with members of Congress who supported Indian removal. Later that year, James Gadsden – a planter who had served in the army under Jackson in Florida – negotiated two treaties. The intention of the US was to remove tribes (called the Seminole, collectively, by the US) from their homes in central Florida and on the Appalachicola River, to the Muscogee reservation in the west. The US also hoped to recover escaped enslaved people who had married into the tribes. Tribal leaders resisted, but sent a delegation west to Fort Gibson to look for suitable land. Corrupt agent John Phagan engineered a fraudulent treaty at the fort; he refused to let the Indigenous delegation read the treaty, in part because it named him to the lucrative position in charge of Seminole relocation. In 1833, additional treaties identified the Muscogee reservation in the west as a new home for Florida tribes, and another treaty at Fort Gibson established boundaries between the western lands of the Cherokee and Muscogee. These treaties exacerbated international relations in Florida to a breaking point in 1835, when the Second Seminole War began. Lewis Cass, negotiated a removal treaty with the Muscogee. Three million acres would be ceded in exchange for money to relocate. Another two million acres would eventually be allotted individually to Muscogee people who intended to stay as citizens in the hostile environment of Alabama. In his new cabinet position, Cass filled the treaty signing room with members of Congress who supported Indian removal. Later that year, James Gadsden – a planter who had served in the army under Jackson in Florida – negotiated two treaties. The intention of the US was to remove tribes (called the Seminole, collectively, by the US) from their homes in central Florida and on the Appalachicola River, to the Muscogee reservation in the west. The US also hoped to recover escaped enslaved people who had married into the tribes. Tribal leaders resisted, but sent a delegation west to Fort Gibson to look for suitable land. Corrupt agent John Phagan engineered a fraudulent treaty at the fort; he refused to let the Indigenous delegation read the treaty, in part because it named him to the lucrative position in charge of Seminole relocation. In 1833, additional treaties identified the Muscogee reservation in the west as a new home for Florida tribes, and another treaty at Fort Gibson established boundaries between the western lands of the Cherokee and Muscogee. These treaties exacerbated international relations in Florida to a breaking point in 1835, when the Second Seminole War began.

Removal in the West, 1832-1839

A team of US treaty commissioners was active throughout the 1830s in the west. They included Montfort Stokes, who resigned from the governorship of North Carolina to take Jackson’s appointment as treaty commissioner; Henry L. Ellsworth, son of a US Supreme Court Chief Justice; J. F. Schermerhorn, a missionary appointed by his friend Andrew Jackson to work on Cherokee and Chickasaw removal who accumulated 400,000 acres in Virginia; and General Matthew Arbuckle, who began his military career as an aide to Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans. These commissioners negotiated treaties -- land cessions, boundary adjustments, compansation for removal -- that facilitated the placement and relocation of Indigenous nations. A treaty with the Caddo was also negotiated by Jehiel Brooks, whose fraudulent behavior as their Indian agent eventually became the subject of a US Supreme Court case.

Black Hawk War Treaties, 1832

Encroachment by US lead miners on Ho Chunk land in Wisconsin, and the appearance of Sauk and Fox families led by Black Hawk in Illinois, led to calls from William Clark and Illinois governor John Reynolds for the extermination of Black Hawk’s band. General Winfield Scott led US forces in a vicious campain against the Sauk and Fox, the Black Hawk War. Lead miner Henry Dodge rose to political prominence during that brief conflict. Subsequently Reynolds and Scott forced removal treaties from the Ho Chunk and Sauk and Fox at Rock Island, Illinois.

Potawatomi, 1832-1837

At the time of the Indian Removal Act, the Potawatomi still lived on numerous reservations in Indiana and Illinois. Between 1832 and 1837, the US negotiated 17 treaties with local Potawatomi bands for the cession of these reservations. The first three were negotiated by Indiana politicians led by former Representative Jonathan Jennings, who had just been forced from his position because of his chronic alcoholism. After Jennings died in 1834, Indian agent William Marshall negotiated four treaties with the Potawatomi and one with the Miami. The next 9 Potawatomi treaties, in 1834, were known as the “whiskey treaties” because of the negotiation methods of commissioner Abel C. Pepper. Pepper had left the medical profession after poisoning a patient, and left the legal profession after bankrupting a client in frivolous law suits; after joining the Masons and becoming an Indian agent in 1829, he was soon promoted to Superintendent for Indian Removal in Indiana, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin. (Pepper also negotiated a treaty with the Miami in 1838.) Another cession of Potawatomi reservations was negotiated in 1837 by John T. Douglas, a former Indian agent and a partner in land speculation with Indiana Senator John Tipton.

Treaty of Chicago, 1833

George Porter, a politician who controlled patronage jobs in Pennsylvania, was appointed Governor of Michigan Territory in 1831. Porter negotiated the cession of reservations in Ohio by Ottawa bands. Some of the Ottawa leaders received title to small tracts of land, as did – inexplicably – Robert Forsyth (the former personal secretary of Lewis Cass) and John Hunt (the brother-in-law of Cass). Forsyth and Hunt also received nearly $20,000 in cash, more than the Ottawa received for their land cession. In addition, thousands of dollars were paid to traders, including the Godroy, Beaufait and Kinzie families who were part of Cass’s treaty making machine. This treaty was a precursor to the Treaty of Chicago, negotiated by Porter later that year. In exchange for the cession of a strip of land northwest of Chicago, the US distributed more than $170,000 to individuals and corporations to whom the Ojibwe allegedly owed money. The Kinzie-Forsyth family walked away in control of more than $100,000 in direct payments or as trustees for other individuals. George Porter, a politician who controlled patronage jobs in Pennsylvania, was appointed Governor of Michigan Territory in 1831. Porter negotiated the cession of reservations in Ohio by Ottawa bands. Some of the Ottawa leaders received title to small tracts of land, as did – inexplicably – Robert Forsyth (the former personal secretary of Lewis Cass) and John Hunt (the brother-in-law of Cass). Forsyth and Hunt also received nearly $20,000 in cash, more than the Ottawa received for their land cession. In addition, thousands of dollars were paid to traders, including the Godroy, Beaufait and Kinzie families who were part of Cass’s treaty making machine. This treaty was a precursor to the Treaty of Chicago, negotiated by Porter later that year. In exchange for the cession of a strip of land northwest of Chicago, the US distributed more than $170,000 to individuals and corporations to whom the Ojibwe allegedly owed money. The Kinzie-Forsyth family walked away in control of more than $100,000 in direct payments or as trustees for other individuals.

Cherokee Removal, 1835

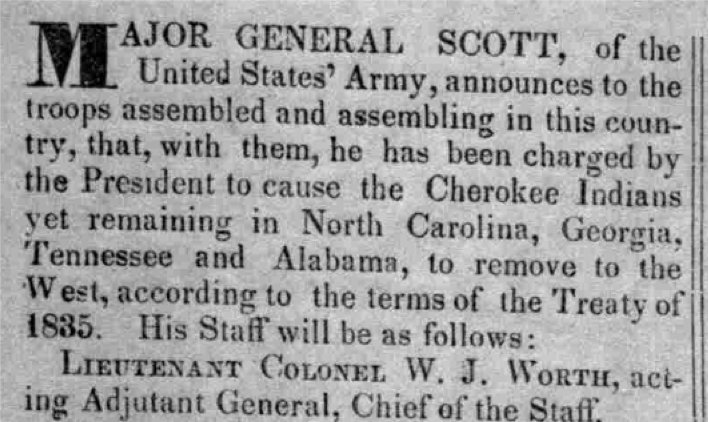

The most iconic instance of Indian Removal – the Cherokee Trail of Tears – occurred subsequent to treaties with the US in 1835. By then, several states had asserted jurisdiction over Indigenous lands, in contravention of the Constitution; gold had been discovered in Georgia, where the decades-old drive to acquire land was already at a fever pitch. As a split among Cherokee leaders widened, the US agent for Cherokee removal, Benjamin Franklin Currey, relied on a violent, state-sponsored, quasi-military group called the Georgia Guard to harass anti-removal Cherokee leaders (e.g. kidnapping Chief John Ross) and to protect pro-removal leaders. In March of 1835, Currey and Rev. J. F. Schermerhorn met in Washington with Cherokee leaders John Ridge and Elias Boudinot to sign a provisional treaty, a cession of all Cherokee land for $5,000,000. Though the Cherokee National Council rejected the treaty, in December the pro-removal faction signed the treaty at New Echota. The US commissioners were Schermerhorn and William Carroll, a land speculator and banker from Tennessee and friend of Andrew Jackson. Other US signers included Currey, Thomas Glascock (whose family had been involved in land speculation since the Yazoo Land Fraud of the 1700s), and Carey Harris (soon to become the most corrupt Commissioner of Indian Affairs). The treaty resulted in the assassination of pro-removal Cherokee signers, and the forced removal of the Cherokee in 1838. For an overview of the Treaty of New Echota from the National Archives, and a copy of General Winfield Scott's orders to remove the Cherokee to the west, see the Columbus (GA) Museum archives object record here.

|

Clearing Western Titles, 1836-1838

In 1836, the western boundary of Missouri served as the limit of white settlement, beyond which eastern Indigenous nations were to be removed. The present-day area of Iowa, too, was already a target for US settlement. But much of this land had been ceded only by the Osage in 1808; several other western nations conceivably could still claim occupancy rights in the region. Consequently, commissioners throughout the Midwest signed a series of treaties with diverse nations to extinguish their aboriginal right of occupancy. The commissioners included Henry Dodge (by then the governor of the newly-created Wisconsin Territory); Zachary Taylor; William Clark (in his last treaty) and his replacement as Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the West, fur trader Joshua Pilcher.

Dodge Treaties, 1836-1837

The aggressive lead miner Henry Dodge, whose armed takeover of Ho Chunk land had led to violence and Ho Chunk removal, was appointed the first governor of Wisconsin Territory in 1836. Within months he started making treaties. In September of 1836, the Menominee ceded tracts in Wisconsin and Michigan; the treaty was attended by one of Wisconsin’s most prominent bankers and land speculators, J. P. Arndt, and his business partner, Territorial Attorney General Henry Baird. Later in the month, the Sauk and Fox ceded a reservation and a strip of land in eastern Iowa; Antoine Leclaire, who would found the site of Davenport weeks later, and George Davenport himself were in attendance. In 1837 Dodge negotiated the White Pine Treaty with the Ojibwe, the cession of a large tract of forested land stretching from the Mississippi River in present-day Minnesota well into Wisconsin. US signers included partners in the American Fur Company Henry Sibley and Hercules Dousman; Dousman would become one of the largest purchasers of timberland from the cession. Within a week after the treaty, three other signers – the notorious Samuel Stambaugh, Indian agent Daniel Bushnell, and John Emerson (owner of Dred Scott) – incorporated a timber company of their own. The aggressive lead miner Henry Dodge, whose armed takeover of Ho Chunk land had led to violence and Ho Chunk removal, was appointed the first governor of Wisconsin Territory in 1836. Within months he started making treaties. In September of 1836, the Menominee ceded tracts in Wisconsin and Michigan; the treaty was attended by one of Wisconsin’s most prominent bankers and land speculators, J. P. Arndt, and his business partner, Territorial Attorney General Henry Baird. Later in the month, the Sauk and Fox ceded a reservation and a strip of land in eastern Iowa; Antoine Leclaire, who would found the site of Davenport weeks later, and George Davenport himself were in attendance. In 1837 Dodge negotiated the White Pine Treaty with the Ojibwe, the cession of a large tract of forested land stretching from the Mississippi River in present-day Minnesota well into Wisconsin. US signers included partners in the American Fur Company Henry Sibley and Hercules Dousman; Dousman would become one of the largest purchasers of timberland from the cession. Within a week after the treaty, three other signers – the notorious Samuel Stambaugh, Indian agent Daniel Bushnell, and John Emerson (owner of Dred Scott) – incorporated a timber company of their own.

Schoolcraft Treaties, 1836-1839

Henry Schoolcraft was appointed an Indian agent by Lewis Cass in the 1820s, just after his book on lead deposits in Missouri kicked off the first great mineral rush. In the 1830s, his territory expanded to include the upper Midwest from Michigan to Minnesota, and he negotiated five treaties for cessions of reservations in Michigan and Wisconsin. Following the model set by Cass, he formed his own small treaty-making machine of relatives (his brother and brothers-in-law), territorial officials and traders. One of Schoolcraft’s brothers-in-law, sutler and fur trader John Hulbert, negotiated a treaty with the Ojibwe for another reservation cession in 1839.

Harris Treaties, 1836-1838

Andrew Jackson appointed his friend Carey Harris to be Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1836. Harris proved to be so corrupt that Jackson left a warning for his successor, Martin Van Buren. Shortly after signing a treaty with the Oneida in 1838, a letter became public that was written by Harris, detailing his plans to profit personally from large-scale fraud in Indian Affairs. He resigned in disgrace and returned to Tennessee.

Dakota, 1837

Alone among the nations of the Midwest, the Dakota (eastern bands of the Seven Council Fires) held a land base that was virtually untouched by the first 60 years of US expansion. They had ceded only a small tract for a fort in 1805, and even that was never proclaimed by any President. Their other treaties with the US were peace agreements after the War of 1812. But with the collapse of the fur trade in 1837, the Dakota travelled to Washington to cede that portion of their homeland that lay east of the Mississippi River in present-day Minnesota and Wisconsin. Carey Harris, head of US Indian Affairs, signed the treaty, but the lead commissioner was his boss: the diplomat, legislator and newly-appointed Secretary of War Joel R. Poinsett, who had recently named a flower from Mexico after himself. Another prominent signer was William J. Worth, an army officer involved in the Black Hawk War and the forced Indian removal under General Winfield Scott. |