|

THE INDIGENOUS TREATY SIGNER SPREADSHEET

The spreadsheet downloadable below is offered as an aid to researchers who want to examine the lives of indigenous treaty signers as individuals who played important historical roles in their own right, and illustrate the complex histories of indigenous nations in North America.

The spreadsheet identifies the indigenous signers using fifteen fields, filled with information from the treaties where available.

TREATY IDENTIFIER FIELDS Every signature by an indigenous representative on all of the official US-Indian treaties is included in the spreadsheet. The treaty in which each of these signatures appears is identified through a number of fields.

INDIVIDUAL IDENTIFIER FIELDS Indigenous signers are indentified inconsistently in the treaties. In some cases, names in indigenous languages are provided; a single signer might have more than one such name. In other cases, the translation of this name into a European language appears in the treaty. In still other cases, names that follow European naming conventions are provided. A single signer might have any or all of these identifiers. Additional information is provided in some treaties that further narrows the identity of the signer(as a relative of another signer, for instance). And many indigenous signers are identifed by titles that indicate their cultural or political roles.

Many indigenous representatives signed more than one treaty. Their names in these cases are often spelled and/or translated inconsistently, and vary in naming conventions from treaty to treaty. A "multisigner code" is assigned to signatures from more than one treaty that were made by the same signer. (This identification is provisional, and will often depend on further research for reliability.)

NATIONAL IDENTIFIER FIELDS

The national identities of indigenous treaty signers are also identified inconsistently in the treaties. Signers of the 1846 "Potawatomi Nation" treaty, for instance, might have been Ojibwe, Ottawa, or Potawatomi. A number of fields have been created in a first attempt to reflect commonalities in national identiy among signers, based on information in the treates. These fields include cultural affiliations (such as the Oceti Sakowin-Seven Council Fires, called "the Sioux" in many treaties; military alliances (which changed over time); or geographic proximity (such as "Middle Oregon").

| TREATY IDENTIFIER FIELDS

Treaty Code: Each treaty is identified here by a unique number. This number is the same for both indigenous signatures, and for the US signers that can be found elsewhere on this website. The Indigenous Signers spreadsheet can be sorted by this code to view all of the indigenous signers of a particular treaty.

Treaty Name (e.g. Delawares 1778)

Treaty Year (Year in which the treaty was signed)

Treaty Date (Specific date of the treaty signing)

Treaty Place (Place at which the treaty was signed. Some treaties were signed in more than one place; listed here is the first or most well known signing place, usually as listed in Kappler's Laws and Treaties vol. 2)

INDIVIDUAL IDENTIFIER FIELDS

Indigenous Name (e.g. Gyantwaia)

Translated Name (Translation of indigenous name into English, Spanish or French, e.g. Cornplanter)

European Convention First Name (e.g. William)

European Convention Last Name (e.g. McIntosh)

Title (e.g. Chief or Sachem or Second Man of Tellico or Interpreter)

Other Identifier (e.g. brother of the Half King or alternative name)

Multisigner Code (The spreadsheet can be sorted by this field to identify all of the treaties signed by Hole in the Day of the Ojbwe, for instance)

NATIONAL IDENTIFIER FIELDS

Alliance (Traditional alliances or tribes that signed treaties together because of geographic proximity, e.g. Seven Council Fires or Middle Oregon Tribes)

Nation (e.g. Mdewakanton -- one of the Seven Council Fires, or Dakota -- eastern bands of the Seven Council Fires)

Town/Band (More specific cultural identifiers such as "from the Town of Tellico" or "Wabasha's village")

|

|  View and Download the Indigenous Treaty Signer Spreadsheet Here View and Download the Indigenous Treaty Signer Spreadsheet Here

|

QUESTIONS ABOUT NATIONAL IDENTITY

Every signature on every official US-Indian treaty is included in either the US Treaty Signer Database (elsewhere on this website) or the Indigenous Signer Spreadsheet below. In some cases, however, a first cursory glance at the treaty signers raises questions about the national identity of some signers. These questions most often arise in the case of Every signature on every official US-Indian treaty is included in either the US Treaty Signer Database (elsewhere on this website) or the Indigenous Signer Spreadsheet below. In some cases, however, a first cursory glance at the treaty signers raises questions about the national identity of some signers. These questions most often arise in the case of

1) Interpreters with one parent who is identified with an indigenous nation, and another parent who is identified with a colonialist nation, are often listed among US signers but in fact may represent an indigenous nation.

2) Signers who may have been installed by the US in leadership positions in an indigenous nations. These individuals may or may not have been recognized as citizens by indigenous nations.

The spreadsheet below lists some of these ambiguities, and indicates whether the signer can be found currently among US signers or indigenous signers. Many of these questions might be resolved easily by tribal historians.

SPREADSHEET: ISSUES OF NATIONAL IDENTITY

| Indig/

US signer

| Signer Last Name

| Signer First Name

| Treaties Signed

| Biography/reason for inclusion

| Sources

| US

| Beaubien

| Meadore B

| Potawatomi 1832 1

Potawatomi Nation 1846

Potawatomi 1861

Potawatomi 1867

| Many signers of 1846 treaty with the Potawatomi walked in both white and indigenous worlds. Moses Scott, B. H. Bertrand, J. N. Bourassa, Perish LeClerc, and Meadore Beaubien were identified as "headmen of the Potawatomi" but had French fathers. They operated at a time when white traders "moved with the Indians, perhaps after losing a campaign to prevent the migration. They sometimes unduly interested themselves in tribal affairs." Meadore Beaubien was the son of a prominent fur trader and an Ottawa woman named Mannabenaqua. As a boy, Meadore accompanied his father to Mackinaw and Milwaukee and worked with him in the fur trade. At 21, he received land in a treaty, and in 1832 he, his brother and his father all received payments in a treaty, in which they were each listed under a differently-spelled surname. In 1833, Beaubien was elected to the Chicago Town Board of Trustees. Around 1840, he moved to Council Bluffs with the Potawatomi, and again moved with them in 1847 to Kansas. He operated stores in these locations, and continued to receive land at treaties through the 1860s. At a treaty in 1867, he is listed among Potawatomi "chiefs, braves, and head-men" that also included B. H. Bertrand, J. N. Bourassa, and G. L. Young. He founded the town of Silver Lake, Kansas and served as its mayor several times.

| Johnson, Simone A. (Dinnneed, D. A., ed.) The French Presence in Kansas, 1673-1854. Thomas Fox Averill Kansas Studies Collection, 2016.

Peterson, Jacqueline. "Goodbye, Madore Beaubien: The Americanization of Early Chicago Society." Chicago History, 1980.

Murphy, Joseph Francis. "Potawatomi Indians of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band." PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1961.

| US

| Beaubien

| Paul H.

| Chippewa Miss. etc. 1863

| Paul Beaubien is a witness to the identity of Ojibwe "half breeds" who were entitled to scrip for land in 1871.

| "Chippewa half-breeds of Lake Superior." Department of the Interior. Washington: House of Representatives, 1871

| US

| Beaulieu

| Paul H.

| Chippewa 1854

Chippewa 1855

Chippewa Red Lake 1863

Chippewa Red Lake 1864

| Paul H. Beaulieu was a member of a prominent Ojibwe-French family. (His father, Clement Beaulieu, was a fur trader. His mother was a daughter of White Raven, a prominent Ojibwe leader in present-day Wisconsin. Paul worked for the American Fur Company at La Pointe, Wisconsin until joining his brother Clement at Crow Wing, Minnesota after an 1847 treaty. In 1852, he started a ferry across the Mississippi in present-day Benton County, Minnesota. When the White Earth Reservation was created in 1867, he preceeded the relocated Ojibwe there and began farming, so is recognized as the first settler at White Earth.

| Paul H. Beaulieu obituary. SCRIBD website

| IND

| Bent

| George

| Cheyenne Arapaho 1867

| George Bent was the son of William Bent and Owl Woman. He spoke English and Cheyenne fluently and attended the finest schools in St. Louis as a boy. As a young man he enlisted in the Confederate army to fight alongside Choctaws and Cherokees. In 1864, at the age of 21, George was captured and paroled home... He sought a safe haven with his mother's family at Black Kettle's camp on Sand Creek but he was still there on November 29, 1864 when Colonel John M. Chivington ... and his soldiers made a killing sweep through the peaceful camp of unarmed women, children and elderly men. Owl Woman and his brother were killed, George was badly wounded... "From that time on," he said, "both in war and in peace, I have been with the Cheyennes." George vowed to avenge the massacre and joined with the Dog Soldiers in attacks on freight trains, towns, ranches and military posts. In 1866 he married Magpie, Black Kettle's niece and they had two children.

| "Bent, St. Vrain and Company," Sangres.com

| US

| Bent

| Robert

| Arapaho Cheyenne 1861

| Robert Bent was the son of prominent trader William Bent. On November 29th, 1864, Robert was forced to lead Colonel John Chivington to the Cheyenne's Sand Creek reservation where over 200 Cheyenne, including his mother, were killed.

| PBS. "William Bent." New Perspectives on the West. Accessed December 29, 2018.

| US

| Bertrand

| Benjamin Henri

| Potawatomi 1861

Potawatomi 1866

Potawatomi 1867

| Many signers of 1846 treaty with the Potawatomi walked in both white and indigenous worlds. Moses Scott, B. H. Bertrand, J. N. Bourassa, Perish LeClerc, and Meadore Beaubien were identified as "headmen of the Potawatomi" but had French fathers. They operated at a time when white traders "moved with the Indians, perhaps after losing a campaign to prevent the migration. They sometimes unduly interested themselves in tribal affairs." Benjamin Henri Bertrand, son of trader Joseph Bertrand and Madeline Bourassa went to school at Carey Mission in Bertrand, Michigan (a town founded by his family). Later, he went to school in Detroit and the Choctaw Academy in Kentucky. Following his schooling, Bertrand worked in his father's trading post for six years, then started his own mercantile business in Bertrand. After 1851, he moved with 650 Potawatomi from Michigan and Indiana to Kansas. In 1866, he set out the town of St. Mary's, where he continued to operate as a trader. At an 1867 treaty, Bertrand is listed among Potawatomi "chiefs, braves, and head-men" that also include J. N. Bourassa, G. L. Young, and M. B. Beaubien.

| Murphy, Joseph Francis. "Potawatomi Indians of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band." PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1961.

| US

| Bertrand, Jr.

| Joseph

| Cheppewa etc. 1833

Potawatomi Nation 1846

| Joseph Bertrand, Jr. was a student of missionary Isaac McCoy in the 1820s. He was married in about 1827 in Bertrand, Michigan (the town named after his fur trading father, in which he was born). A widower by 1836, he married again that year in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and moved with his family when the Potawatomi were removed to Kansas in 1840. Bertrand worked as a trader and interpreter and again moved to the Kaw Reservation in 1848 in another Potawatomi relocation, serving as one of the delegation that selected the site.

| Murphy, Joseph Francis. "Potawatomi Indians of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band." PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1961.

| US

| Bird

| James

| Blackfeet 1855

| James Bird was the son of a Hudson Bay trader and a Cree woman, and worked as a trader, trapper and interpreter, both independently and for various trading companies, in the 1820s and 1830s. He became influential among the Blackfeet and helped direct their trade to his current employers. In the 1840s he became a guide to settlers in the Red River region, where he and his family moved in 1856. In the 1880s they relocated to a reservation in Montana.

| David Smyth, “Bird, James (d. 1892),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 10, 2020

| US

| Blanchford

| Henry

| Chippewa 1842

Chippewa Miss. Sup. 1847

Chippewa 1854

| Born Francois Descarreaux, Henry Blanchford was placed in the Mackinaw Mission School, where he was re-named after the pastor of a church in Michigan. He remained a student and apprentice at the school until 1831. In 1834, Blanchford arrived in La Pointe, Wisconsin and found employment as an interpreter and missionary headquartered at the Pokegama Mission in Minnesota. After the mission at Odanah, Wisconsin came under the control of the Presbyterian Church, Blanchford became the sole pastor of the mission. He translated a series of school textbooks, scriptures, and other books into Ojibwe.

| Lehman, Julia, and Jasmine Krotzman, eds. "Transcription and Works Cited for Research of Letters 14 and 15, Charles Francis Xavier Goldsmith's Collected Papers." Accessed September 18, 2019

| IND

| Bossman

| Washn.

| Potawatomi Nation 1846

| Bossman's first name is listed as "Wah-n" or "Wash'n" in various editions of Kappler. He is identified as "Mackinaw Beauchemie" by S. A. Johnson. "Although Mackinaw Beauchemie 1421 lived among the Shawnee Indians in Kansas, he was considered a Pottawatomie. The son of a Frenchman and a Chippewa woman, he was born in Mackinaw, Michigan, therefore his given name. It is surmised that his father was a colonel in the French army who was about to be shipped back to France after General Wolfe defeated the French forces. When he was arranging to have his two sons placed on board a ship transporting troops back to their native land, their mother, Maune, the daughter of a Chippewa chief managed to flee with her children, finally finding refuge among the Pottawatomies among whom Mackinaw was raised.

| "The Pottawatomie Baptist Manual Labor Training School," Kansas Historical Society Website

Johnson, S. A. The French Presence in Kansas, 1673-1854. Thomas Fox Averill Kansas Studies Collection, 2016

| IND

| Bourassa

| J. N.

| Potawatomi Nation 1846

Potawatomi 1861

Potawatomi 1866

Potawatomi 1867

| Many signers of 1846 treaty with the Potawatomi walked in both white and indigenous worlds. Moses Scott, B. H. Bertrand, J. N. Bourassa, Perish LeClerc, and Meadore Beaubien were identified as "headmen of the Potawatomi" but had French fathers. They operated at a time when white traders "moved with the Indians, perhaps after losing a campaign to prevent the migration. They sometimes unduly interested themselves in tribal affairs."

| Murphy, Joseph Francis. "Potawatomi Indians of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band." PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1961.

| IND

| Brown

| Adam

| Wyandot etc. 1805

Chippewa etc. 1808

| Adam Brown was a white child captured by the Wyandot, and raised as a member of the nation. Brown fought with the Wyandot and British in wars against the US, and signed treaties as a Wyandot representative. Brownstown, Michigan, site of several US-Indian treaties, was named after him. Brown's grandchildren included Matthew Mudeater, a Wyandot treaty signer who led his nation during their removal to Oklahoma; and Quindaro Nancy Brown, who married US treaty signer Abelard Guthrie.

| “Adam Brown.” Wyandot Nation website; “BNO Walker.” Wyandot Nation website, citing “A Personal Sketch of Bertrand Nicholas Oliver Walker,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 6, No. 1 (March, 1928)

| US

| Campbell

| Antoine Joseph

| Sioux Mde. Wahpak. 1858

Sioux Siss. Wahpet. 1858

| In 1862, Antoine Joseph Campbell -- a close friend of Little Crow -- was in Yellow Medicine during the Dakota War. He was tried with the Dakota by a military tribunal, but acquitted. He died more than 50 years later in Lac qui Parle County, Minnesota.

| Atkins, Annette. Creating Minnesota: A History from the Inside Out. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009.

| US

| Campbell

| Scott

| Sioux etc. 1825

Sauk Foxes etc. 1830

Sioux 1836 2

Chippewa 1837 2

Sioux 1837

| Scott Campbell, son of a Scottish trader and a Dakota mother, was taken east by Meriwether Lewis as a young boy. Upon the death of Lewis in 1809, he returned to his family. By 1819, he was licensed to trade for James Lockwood (AFC) above Prairie du Chien. In 1834, he acted as interpreter for agent Lawrence Taliaferro at Fort Snelling. He provided information to Edmund Ogden for a glossary of Dakota words. While living at the St. Peter settlement in 1837, he went to Washington, DC as an interpreter for a treaty delegation. In 1843, he purchased several blocks of what is now downtown St. Paul, Minnesota, which he sold in 1848. Two of his sons were hung in the aftermath of the Dakota War of 1862.

| Historical Society, Minnesota. Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society: Volume 8. St. Paul, MN: Published by the Society, December 1908.

Atkins, Annette. Creating Minnesota: A History from the Inside Out. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2009.

Neill, Edward D. Occurrences in the Vicinity of St. Paul Minnesota: Before its Incorporation as a City. D. Mason and Company, 1890

Newson, T. M. Pen Pictures of St. Paul, Minnesota, and Biograohical Sketches of Old Settlers, From the Earliest Settlement of the City, up to and Including the Year 1857, Volume 1. St. Paul: Published by the author, 1886.

| US

| Caron

| Charles

| Menominee 1848

| Charles Caron (or Carron) was a son of Pierre Antoine Grignon, and therefore a half-brother of Robert Grignon, who signed the same 1848 Menominee treaty.

| Barnum. "Barnum Family Genealogy 1350 to the Present." Accessed January 4, 2019

| IND

| Carr

| Thomas

| Creeks 1832

Creeks Seminole 1845

| "Thomas Carr, a half blood, who married a full blood Creek. The father of Thomas Carr was a white man and married a Creek Indian woman. Thomas Carr came to the Indian Territory with the McIntosh party of the Creek tribe."

| Hill, Luther B. A History of the State of Oklahoma, vol. 2. Oklahoma: Lewis Publishing Co., 1910

| US

| Carr

| Paddy

| Creeks 1827

| Paddy Carr was the son of a Creek woman and an Irish father but raised by John Crowell, an Indian agent. In 1826, Carr accompanied a Creek delegation to Washington, DC as an interpreter, where he“often gave [speeches by the Creek representatives] additional vigor and clearness, by the propriety and force of the language in which he clothed it.” He married the daughter of a Colonel Lovett and went into the fur trade, accumulating property and 70-80 slaves. Carr fought with the United States in 1836 against the Creek in the Creek War. He then marched to Florida “as second in command of about five hundred Creek warriors, who volunteered their services to the government.” Another of his wives was a daughter of Creek leader William McIntosh.

| White, George. Historical Collections of Georgia: Containing the Most Interesting Facts.. Pudney & Russell, 1855.

M'Kenney, Thomas L., and James Hall. History of the Indian Tribes of North America. Philadelphia: Frederick W. Greenough, 1838.

| IND

| Colville

| George

| Cherokee 1819

| "The first town in the county was laid out by Maj. John Walker, and named in honor of John C. Calhoun. Walker was part Cherokee, and had been allowed a large reservation on the north bank of the Hiwassee, and upon this reservation he established the town. Among the first settlers of the town were ... George Colville."

| History of Tennessee. Chicago and Nashville: Southern Historical Press, 1887

| US

| Crawford

| Charles

| Sioux Siss. Wahpet. 1858

Sioux Siss. Wahpet. 1867

| Charles Crawford was the son of a Dakota woman and a white trader, and a relative of Joseph Renshaw Brown. In 1862, at the time of the Dakota War, he was a clerk at the Yellow Medicine Indian agency. Crawford was acquitted twice in the trials of Dakota people after the war, then joined General Henry Sibley's troops as a scout on a punative campaign against the Dakota. After 1866, he lived on the Sisseton Reservation, and in 1879 was licensed as a Presbyterian preacher in Good Will, South Dakota.

| Anderson, Gary Clayton. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1863. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2010.

| US

| Decouagne

| Louis

| Kaskaskia 1803

Sioux of the Lakes 1815

Potawatomi 1815

Piankeshaw 1815

Teton 1815

Sioux of St. Peters 1815

Yankton Sioux 1815

Makah 1815

| Louis Jefferson Decouagne (or Ducoigne) was the son of a French/Indian leader of the Tamaroa, who were part of the Illiniwek Confederacy. He signed a treaty in 1803 as a member of the Kaskaskia tribe, was an interpreter at the Portage des Sioux treaties in 1815, and signed again as a member of the Kaskaskia tribe at a treaty in 1818. Du Quoin, Illinois is named after his father.

| Fitzgerald, Scott. "Jean Baptiste Ducoigne: Chief of the Kaskaskias." The Southern Illinoisan, October 11, 2011.

| IND

| Duchasin

| Joseph

| Quapaw 1824

Quapaw 1833

| One treaty signed by Duchasin indicates that he was a white trader; the other indicates that he was Quapaw. "Due from the Quapaw tribe of Indians to … Joseph Duchasin… $30." "There shall be granted by the United States, to the following persons, being Indians by descent, the following tracts of Land: … To Joseph Duchassin, one quarter section." Listed in government documents as an interpreter to the Quapaw in 1837, most other men in this position being white.

| Official Register of the United States. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1838

| US

| Edwards

| John W.

| Caddo 1835

| John W. Edwards was a Quapaw interpreter, though there is some question about whether he knew the Caddo language. (He was the interpreter at a Caddo-US treaty.) John was "a sickly person until his death" and "subject to fits." The Caddo hired a spy to listen to Edwards' interpretation at the treaty, who reported that Edwards misrepresented the Caddo negotiators.

| "The Caddo Indiant Treaty." H.R. No. 1035, 27th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1842)

Teran, Gereral Manuel de Meir y. Texas by Teran: The Diary kept by General Manuel de Meir y Teran on his 1828 Inspection of Texas. University of Texas Press, 2000.

| US

| Garreau

| Pierre (2)

| Fort Berthold 1866

| Pierre Garreau was the Mandan step-son of trader Antoine Garreau. Pierre became a trader at Fort Clark and at Fort Berthold, where he interpreted for the army, and for Pierre Chouteau, Jr., and other traders. Garreau died in 1870 when his hut caught fire in the night.

| Lounsberry, Clement Augustus. Early History of North Dakota: Essential Outlines of Amerian History. Washington, D.C. Liberty Press, 1919.

Wischmann, Lesley, and Andrew Erskine Dawson. This Far-Off Wild Land, the Upper Missouri Letters of Andrew Dawson. Norman Oklahoma: The Arthur C. Clarke Company, 2013.

Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. vol. 1. Bismark, ND: Tribune, State Printers and Binders, 1906.

| US

| Hamlin

| Aug

| Ottawa Chippewa 1855

| Aug Hamlin accompanied William Blackbird (brother of Ottawa treaty signer Andrew J. Blackbird) to Rome, where William was studying for the priesthood. Hamlin relayed the news of William's death under mysterious circumstances to the Blackbird family. When Hamlin returned to the United States, he served as an interpreter, from 1836 to 1861.

| Blackbird, Andrew J. History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan. Ypsilanti, MI: The Ypsilantian Job Printing House, 1887.

| US

| James

| Joseph

| Kansa Tribe 1859

Kansa 1862

| “Joe Jim, Jr.” was the son of a Kansa/Osage/French interpreter for the US who guided missionary Isaac McCoy to Kansas, and married a Kansa woman who was the daughter of White Plume. In the 1850s, James' arm was amputated, curtailing his travels. In 1858 he he was hired again as an interpreter for the US government, and the following year providing information for ethnologist Lewis Henry Morgan. In 1867 he accompanied a Kansa delegation to Washington, and continued to live with the tribe until their emigration to Oklahoma in 1873. In 1868 he rode to Topeka (a town he had named) to alert the governor that Comanche were attacking the Kansa in Council Grove; traveling with him was an 8-year-old nephew, Charles Curtis, who was later US Vice President. He established a homestead on the Arkansas River, and at the time of his death was “the oldest of the Kaw Indians.”

| Parks, Ronald D. The Darkest Period: The Kanza Indians and Their Last Homeland, 1846–1873. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

Morgan, Lewis Henry, and Leslie A. White, ed. The Indian Journals, 1859-62. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1993.

| IND

| Johnson

| John

| Chippewa Miss. etc. 1863

Chippewa Miss. 1867

| Enmegahbowh (John Johnson), Ojibwe/Ottawa moved from his birth place near Toronto in 1832 to attend a Methodist missionary school near Sault Ste. Marie. From 1835 to 1837 he served as an interpreter at Methodist Episcopal missions and from 1837 to 1839 attended the Ebenezer Manual Labor Training School in Jacksonville, IL. He became an Assistant Methodist Episcopal missionary at Little Falls, MN in 1839, and married a niece of Hole in the Day. He also worked as a missionary Whitefish Lake, Sandy Lake, Leech, Cass and Red Lakes until 1845, when he “switched from Methodism to Episcopalianism.” In 1852 he co-founded St. Columba Mission at Gull Lake where he was ordained a deacon, and in 1867 became “the first American Indian Episcopal priest,” ordained by Henry Whipple. In 1868 he moved to the White Earth Reservation.

| In Honor of the People. "enmegahbowh." Accessed April 11, 2019.

| IND

| Jones

| John T.

| Potawatomi Nation 1846

Ottawa Blanch. etc. 1862

Seneca etc. 1867

| Jones, the son of an Englishman and an Ojibwe woman, grew up with a sister at Mackinac. As a boy he hopped a Detroit freight ship to Detroit, where after several years he became homeless. He was found by Baptist missionaries and taken to the Carey Mission School in MI. After four or five years there, missionary Isaac McCoy sent him to study at Hamilton College.After four years there, he studied at Choctaw Acadamy in Kentucky as a teacher for a year. After a brief stint at interpreter at Sault Ste. Marie, Jones moved to Kansas with the Potawatomi, and “was a member of their tribe.” When the Potawatomi and Ottawa moved to the same reservation, he “joined the Ottawas, of which tribe he remained a member until his death.” He purchased a farm for $1,000 and in 1850 built a store near Ottawa, KS, and ran “the main country hotel in Eastern Kansas.” The storewas burned by “border ruffians” in 1856. As a member of the Ottawa tribal Council, Jones became a participant in the establishment of Ottawa University,a land fraud perpetrated by Jones, Indian agent Clinton Hutchinson and others. “Bi-cultural Ottawas like John Tecumseh Jones exploited tribal disunity for their own ends.” A John T. Jones served as a "proxy" Representative at an 1840 Masonic Convention to organize a Grand Lodge in Illinois.

| Kansas Collection Books. " William G Cutler's History of the State of Kansas, Era of Peace, pary 44." Accessed January 17, 2019

Wright, Dudley, ed. Gould's History of Freemasonry. Vol. 4--6. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936

Kugel, Rebecca. Review of Tribal Dispossession and the Ottawa Indian University Fraud, by William E. Unrau and H. Craig Miner. UCLA Historical Journal 6 (1985): 134-135.

| US

| Juzan

| Charles

| Choctaw 1805

| Son of a French trader and a Choctaw mother, Juzan served as the US Interpreter for the 1805 Choctaw treaty and represented the Choctaw. During the Creek War in 1813 his family sided with the Americans. He operated a trading post on Lost Horse Creek (Coosa, Alabama) in the 1820’s and 1830's, and allegedly amassed a fortune by robbing travelers. He and his family received land in the 1830 treaty at Dancing Rabbit Creek. He was also a slaveowner.

| Halbert, H.S., and T.H. Ball. The Creek War of 1813 and 1814. Chicago, IL: Donohue & Henneberry, 1895.

Davis, Patricia Lightsey. The History of Daleville Mississippi. Meridian, MS: Lauderdale County Department of Archives and History, n.d.

Thrapp, Dan L. Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography. Vol. 2. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991.

Mississippi Board of Choctaw Indians. "Treaty with the Choctaws, 1830." Accessed May 15, 2019.

Wilson, Michael D. "Treaty with the Choctaw, 1830." University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Accessed May 15, 2019.

Kidwell, Clara Sue. Choctaws and Missionaries in Mississippi, 1818-1918. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997

| US

| Labussier

| Francois

| Sauk and Foxes 1836 1

Sauk and Foxes 1836 2

Sauk and Foxes 1836 3

| Francois Labussier was a French-Sac metis who served as Keokuk's interpreter.

| Trask, Kerry A. Black Hawk, The Battle for the Heart of America. Henry Holt and Company, 2013.

| IND

| Le Clerk

| Pierre or Perish

| Potawatomi Nation 1846

| Many signers of 1846 treaty with the Potawatomi walked in both white and indigenous worlds. Moses Scott, B. H. Bertrand, J. N. Bourassa, Perish LeClerc, and Meadore Beaubien were identified as "headmen of the Potawatomi" but had French fathers. They operated at a time when white traders "moved with the Indians, perhaps after losing a campaign to prevent the migration. They sometimes unduly interested themselves in tribal affairs."

| Murphy, Joseph Francis. "Potawatomi Indians of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band." PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1961.

| US

| Loise

| Paul

| Kansa 1825 1

| As a treaty interpreter, Paul Loise (or Louise) translated from Osage into French. He resigned from his job as interpreter and "hired man" in St. Louis in 1827, with a plan to lead an Osage delegation to France, "as a pecuniary speculation"

| Osage Nation of Indians Judgement Funds. Washington: US Senate, 1972

Barry, Louisa. "William Clark's Diary." Kansas Historical Society Website. Accessed April 15, 2019

| US

| Mackey

| Middleton

| Choctaw 1805

Choctaw 1816

Choctaw 1820

Choctaw 1830

| Middleton Mackey was the son of Revolutionary War soldier James Mackey and Alice Ford. He was "stolen by the Creek Indians, when a boy, and his descendants are now in that Nation, he having married an Indian woman." Mackey received land in a treaty, as part of a group that included both white and Choctaw people. He was an interpreter for the US and a member of the "Pitchlynn Faction," a group hired by Andrew Jackson to spread propoganda among the Choctaw to win their acquiescence to removal. Mackey was identified as "evil" and distrusted by anti-removal Choctaw

| Thorne, Barry E. "David Folsom and the Emergence of Choctaw Nationalism." Master's thesis, Oklahoma State University, 1981

Doughtie, B. M. The Mackey's (variously spelled) and allied families, vol. 2. Decatur, GA?: 1957

| IND

| Marksman

| Peter

| Chippewa Miss. Sup. 1847

Chippewa 1854

| Marksman was an Ojibwe from present-day Michigan. His original name was supposedly “Madwegwaneyaash, meaning "[Arrow]-Feathers Are Heard in the Breeze, which was translated as “marksman” when he was converted to Christianity about 1833. He became a Methodist Episcopal missionary, primarily among the Potawatomi, burning the “bad medicine” of his audiences after preaching to them. He was still a preacher in 1885.

| Revolvy.com. "Peter Marksman". Accessed April 21, 2019

Keepers of the Fire: Hannahville Indian Community. "Hannahville History". Accessed April 21, 2019

| IND

| Nelson

| Henrys

| Kansa 1846

| Nelson Henry (listed as Henrys in the treaty) was a missionary among the Kansa tribe near Jackson, Missouri. In 1844, when the Methodist Episcopal Church split over the issue of slavery, Henry aligned his mission with abolitionists. He is also referred to as “a young, educated, Kansa Indian.”

| Ellinghouse, C. R. Old Wayne: A Brit’s Memoir. Xlibris, 2010

Barry, L. “Kansas Before 1843: A Revised Annals, Part Fifteen.” Kansas Historical Quarterly, (Fall?) 1964. Topeka: Kansas Historical Society, 1964

| US

| Ogee

| L. H.

| Winnebago etc. 1828

| Joseph (L. H.) Ogee was a French-Winnebago man who worked as an interpreter at Peoria as early as 1824. He also owned and piloted a ferry on the Rock River until he sold it in 1830 and provided his interpretation services in Chicago. While he lived there, his cabin near the ferry was the local courthouse.

| Earlychicago.com. Based on Ulrich Danckers et al. A Compendium of the Early History of Chicago to the Year 1835, When the Indians Left. River Forest, IL: Early Chicago, Inc., 2000

Tregillis, Henry Cox. The Indians of Illinois. Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, 1991.

| US

| Parker

| Ely. S.

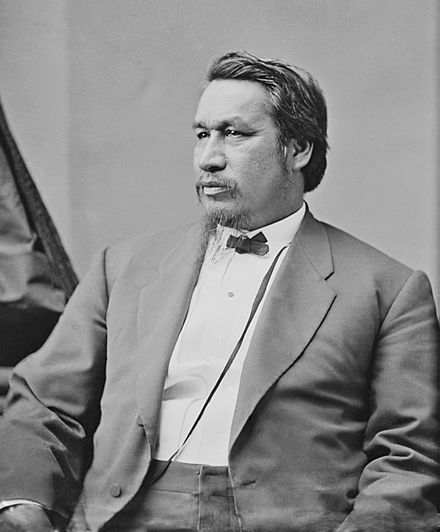

| Cherokee etc. 1865

Creeks 1866

Choctaw Chickasaw 1866

| Ely S. Parker was born on the Tonawanda Reservation with the name Ha-sa-no-an-da, but was baptized under his "European" name. His family was Seneca and his father was a Baptist minister. Parker was educated at a missionary school, attended college, and read for a law degree in Ellicottville, New York. He was not admitted to the bar because he was not considered a US citizen. With the help of Lewis Henry Morgan, a budding anthropologist whom he met in a bookstore, Parker was admitted to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and worked as a civil engineer until the Civil War. His assignments included work on improvements to the Erie Canal and projects in Galena, Illinois, where he met U. S. Grant. Parker was an interpreter in treaty negotiations and, in 1852, made a sachem of the Seneca. At the start of the Civil War, he was denied permission to start an Iroquois regiment or even join the Union Army, but with Grant’s help was commissioned a captain in 1863. He was Grant’s adjutant in the Chattanooga campaign and, later, as lieutenant colonel, Grant’s military secretary. Parker helped draft the surrender documents signed by Robert E. Lee. After the Civil War, Parker was a member of the Southern Treaty Commission that negotiated agreements with tribes allied to the Confederacy. He resigned from the army in 1869 and was appointed US Commissioner of Indian Affairs for two years. After investing in the stock market, he was financially ruined by the “collapse of 1873." He was appointed to a bureaucratic role in the New York Police Department, but died in poverty on January 20, 1897.

| Native Heritage Project. "Ely Samuel Parker, Seneca." Accessed April 22, 2019.

| US

| Parks

| Joseph

| Seneca etc. 1831

Shawnee 1831

| Joseph Parks was of Shawnee descent and grew up in the home of General Lewis Cass, who later hired him as an interpreter for the Indian service. In 1833, Parks was "entrusted by the government with the removal of his band" from Ohio to Kansas. He served as captain of one of two Shawnee companies during the Seminole Wars. As leadership among the Shawnee transformed from hereditary to elected positions, he became a chief. Parks owned land in Kansas and Missouri.

| Kansas State Historical Society. Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, Volume 10. Topeka: State Printing Office, 1908.

Calloway, Collin. The Shawnees and the War for America. New York: Penguin, 2007.

| US

| Peoria

| Baptiste

| Delawares 1829 2

Piankeshaw Wea 1832

Seneca Shawnee 1832

Kaskaskia etc. 1854

Miami 1854

| Baptiste Peoria worked as an interpreter, speaking French, English, Potawatomi, Delaware, Shawnee, and the languages of the Iroquois Confederacy. Around 1832, he moved to what is now Kansas as head of the Confederated Tribes of the Kaskaskia, Peoria, Wea, and Piankeshaw. As a partner in the Paola Town Company, he was a founder of Paola, Kansas. The confederated tribes relocated to Oklahoma in the 1860s, and he was appointed a "Special Agent" by the US.

| "Baptiste Peoria acting as a 'Special Agent' of the US Government." Miami County (OH) History Museum website. Accessed January 14, 2020

Adams, George. George W. Martin. Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, Volume 12. Kansas: State Printing Office, 1912.

City of Paola. "History of Paola." Accessed January 2, 2019.

| IND

| Picotte

| Chas. F.

| Yankton Sioux 1858

Fort Berthold 1866

| Picotte, son of a French trader and a Yankton woman, was educated in St. Louis and became "an influential member of the Yankton band." He signed the Yankton treaty of 1848 as Eta-ke-cha, and received a land allotment of 640 acres. He was also a partner with J. B. S. Todd in the Upper Missouri Land Company, which established to town of Yankton on Picotte's land. With Todd he was a lobbyist for the organization of Dakota Territory. He joined the Dakota [Territorial] Militia in 1862, during the Dakota War. Picotte constructed the Territorial capitol building, and was an incorporator of the Dakota Southern Railroad Company.

| "Pa-la-ne-a-pa-pa, Struck by the Ree." Akta Lakota Musum & Cultural Center website. Accessed Janurary 14, 2020

"Charles Picotte Is A Mystery." Yankton Daily Press & Dakotan, September 15, 1999

| IND

| Rice

| Luther

| Potawatomi 1832 2

Chippewa etc. 1833

| Rice (also known as Naoquet) was a mixed-race Potawatomi educated at the Carey Mission School in Michigan. Prior to the Potawatomi removal treaty of 1832, he auctioned off his interpreter services among the US and several Potawatomi bands, and secured a job with US agent Abel Pepper.

| Bowes, John P. Exiles and Pioneers: Eastern Indians and the Trans-Mississippi West. Cambridge University Press. New York, 2007.

| US

| Scott

| Moses A.

| Potawatomi Nation 1846

| In the 1846 treaty with the Potawatomi, the national identities of many signers difficult to determine. A Moses H. Scott is listed as one of the headmen of the Potawatomi, but M. H. Scott is listed among the US witnesses. In the 1840s "Moses A. Scott," was a licensed trader to the Potawatomi, at a time when white traders "moved with the Indians, perhaps after losing a campaign to prevent the migration. They sometimes unduly interested themselves in tribal affairs."

| Murphy, Joseph Francis. "Potawatomi Indians of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band." PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1961.

| IND

| Shane

| A./Anth'y

| Wyandot etc. 1817

Wyandot 1818 1

Delawares 1829 2

Shawnee etc. 1832

Kaskaskia etc. 1832

Piankeshaw Wea 1832

Kickapoo 1832

| Anthony Shane was the son of a French Canadian father and Ottawa mother. He fouught with the indigenous alliance against US expansion until the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, then became an interpreter, messenger, scout and advisor to William Hull and other US officials in Michigan and Ohio. He joined the US military in the War of 1812. In 1817 he received 640 acres in a treaty for his services, and moved west with the Shawnee on their removal to Kansas.

| Frech, Harrison. "Anthony Shane, Founding Father." Rockford, OH website

| IND

| Shaw

| Jim

| Comanche etc. 1846

| Jim Shaw was a Delaware man who arrived in the western Plains by 1841. He was a scout, interpreter and diplomat, negotiating with the Comanche on behalf of Sam Houston during Texas' independence, and for the US as a US Indian agent.

| Richardson, R. N. and Anderson, H. A. "Shaw, Jim." Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association

| IND

| Walker

| John R.

| Wyandot etc. 1817

| William Walker was captured by the Delaware and transferred to the Wyandot, among whom he was raised by Adam Brown. Walker lived with Brown until he married the Wyandot daughter of US treaty signer James Rankin, and became a US treaty negotiator. William Walker’s children included Wyandot treaty signers John R. Walker and William W. Walker, who became the first provisional governor of Nebraska Territory.

| “Adam Brown.” Wyandot Nation website; “BNO Walker.” Wyandot Nation website, citing “A Personal Sketch of Bertrand Nicholas Oliver Walker,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 6, No. 1 (March, 1928)

| IND

| Walker

| William

| Shawnee 1831

Wyandot 1836

Ottawa 1831

| William Walker was captured by the Delaware and transferred to the Wyandot, among whom he was raised by Adam Brown. Walker lived with Brown until he married the Wyandot daughter of US treaty signer James Rankin, and became a US treaty negotiator. William Walker’s children included Wyandot treaty signers John R. Walker and William W. Walker, who became the first provisional governor of Nebraska Territory.

| “Adam Brown.” Wyandot Nation website; “BNO Walker.” Wyandot Nation website, citing “A Personal Sketch of Bertrand Nicholas Oliver Walker,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 6, No. 1 (March, 1928)

| US

| Wells

| William

| Wyandot etc. 1795

Delawares etc. 1803

Delawares etc. 1805

Delawares etc. 1809

Miami etc. 1809

| William Wells was orphaned shortly after his family moved to Kentucky. When he was twelve years old (1782), he was taken captive by the Miami and adopted into the tribe. Around 1788, he reconnected with his brothers in Louisville, but decided to remain with the Miami. When a raid by General James Wilkinson killed his Wea wife and child, Wells (or Apekonit, his Miami name) organized 300 Miami soldiers to fight against the US in St. Clair's Defeat. He served as a Miami scout in the Northwest Indian War (also called Little Turtle's War) after marrying a daughter of Little Turtle. In 1793, Wells again connected with his brother, and with Little Turtle's agreement joined Anthony Wayne's Legion of the United States. He was wounded at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, and after the Treaty of Greenville (1795), he was made the US Indian agent to the Miami at Little Turtle's request. His fifteen years at Fort Wayne were marked by changes in political fortunes as he and his rival, John Johnston, rose and fell in the favor of Presidents and Governor William Henry Harrison. US politicians distrusted Well's close relationship with Little Turtle, but the relationship helped keep the Miami from joining Tecumseh's confederacy. Wells led Miami warriors to the defense of Fort Dearborn in 1812 and was killed by Potawatomi warriors in the battle. Wells County, Indiana is named after him.

| Heath, William. William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015.

| US

| Williams

| Eleazer

| Stockbridge 1848

| Eleazer Williams, described unreliably as being "of mixed Indian-white parentage," trained as a missionary at Longmeadow, Massachusetts, and attended Dartmouth. He became an Episcopal missionary to the Oneida in New York in 1815. Williams developed a plan to create an "Indian empire" in Wisconsin, with himself as emperor. He moved with the Stockbridge Munsee band to Green Bay in 1821, and began lobbying the federal government for a land cession from the Menominee and Ho Chunk. The government eventually supported the plan because it removed indigenous people from New York, and negotiated a treaty with the Menominee in 1831 to provide land for the "the New York Indians." Williams married a Menominee woman and secured land for himself, but his leadership was repudiated by the Menominee. By 1839, he was claiming to be the "Lost Dauphin" of France, Louis XVII. He tricked his mother into claiming he was adopted. In the 1850s he was signing manifestos as “L. D.” (Louis, Dauphin), and was borrowing money on the promise of his inheritance of the French throne. He “died in poverty and obscurity” on August 28, 1858.

| Wisconsin Historical Society. "Williams, Eleazer 1788-1858." Accessed May 6, 2019.

Hondrocostas, Nicholas. Eleazer Williams: missionary and pretender, 1789-1858. University of Wisconsin--Madison, 1959.

| US

| Wright

| George

| Seneca etc. 1867

| George Wright was "of Delaware and Wyandot descent;" his grandmother was an enslaved woman captured in Guinea and sold to a Delaware slaveholder. In 1850, Wright moved with the Wyandot to Kansas, where he worked as a government interpreter for sixteen years. During the Civil War, he spent two years as a Union soldier.

| Connelley, William Esley. Wyandot Folk-lore. Crane, 1999

|

|